Criticising Empire: J. M. Coetzee's Barbarians

Somewhere in the desert there is a town with no name, a settlement cut off from the rest of the civilised world. It relies on the produce of its own livestock, its wheat farms, and belongs to an empire on the brink of war.

Dangerously, the town sits slap bang on the border of the empire’s territory, and being alone in the fields, it faces the wild frontier.

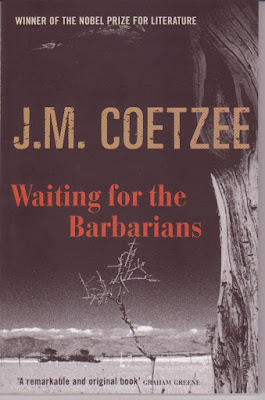

Beyond, there are barbarians — dissidents in the eyes of this lonely desert kingdom. For reasons of public safety, military men have arrived in the town with a group of interrogators, and its up to an unnamed magistrate to mediate matters. The sun beats down, tensions run high, and the town anticipates imminent conflict: This is the setting of J. M. Coetzee’s breakthrough novel, Waiting for the Barbarians (1980).

Who exactly are these barbarians? No-one seems to know. Chief inquisitor Colonel Joll captures the confusion of the times and detains a group of local fisherfolk to find answers.

But it’s all a worldly performance. These people are, in fact, innocent. Yet the Colonel asserts their treachery to the empire using the tool of bureaucratic language. Saying to the magistrate: “I have a commission to fulfil, Magistrate. Only I can judge when my work is completed” (p. 12). His words create a veneer to mask the emptiness of his false quest for so-named ‘truth’.

There is even a possibility that the barbarians might be a government-mandated fiction built on a series of crafty lies. Before too long, the magistrate falls into a labyrinth of self-questioning moods, a dangerous position to be in as he begins to wonder what is really happening.

Waiting for the Barbarians is a deeply political novel, written in an allegorical style. From the offset, the reader confronts an uncomfortable situation: there are few proper nouns in this narrative. The “fishermen”, “the town”, “the frontier”, “the magistrate”, “the barbarians”, “the empire” — nothing has a particular name, meaning this could be set anywhere in time or space.

Therefore, we must understand this story at a deeper level — as a universal criticism of empirical regimes, repressive governments throughout history.

When the magistrate begins to investigate the Colonel’s activities, the novel swiftly illustrates its politically framed agenda. Questioning a young lieutenant on the torturing of fisherfolk the magistrate receives a revelatory response. ‘“I spoke to him,” the [lieutenant] tells me, “but all he said was, ‘Prisoners are prisoners’. I decided it was not my place to argue with him [the Colonel]”’ (p. 23).

The Colonel’s reply is a counter-explanation, a way to avoid telling the truth. Saying something like “prisoners are prisoners” is a tautological statement, that is, meaningless but made to appear sensible. In his philosophical criticism of such speech acts, the critic Roland Barthes once tarnished tautologies for their utter banality. “Tautology,” he wrote

testifies to a profound distrust of language, which is rejected because it has failed. Now any refusal of language is a death. Tautology creates a dead, a motionless world (from Mythologies, p. 181).

Avoiding any painful, gory details, the Colonel kills any potential opportunities for anyone to criticise the empire’s doings, nips them in the bud.

Fast forward through a plot that sees the magistrate charged with treason, this novel finds that an empire’s greatest enemy is far closer to home — a human being’s capacity for emotion: to empathise with victims.

Empathy, the ability to share the feelings of others, is a powerful weapon. When a nation-state entrenches an unethical system of values into the minds of its citizenry, how else would citizens question a government’s actions? “You are an obscene torturer! You deserve to hang!” the magistrate screams at the Colonel in a wholly indifferent office. The Colonel just smiles back: “Thus speaks the judge, the One Just Man” (p. 125).

The magistrate ends up enduring the fate of a prisoner. He lives in squalor in a damp cell. His sympathy for the previous inhabitants, tortured victims, has led him to re-live the experiences of the voiceless, the dead prisoners.

I daily become more like a beast or a simple machine, a child’s spinning wheel [. . .] I respond with movements of vertiginous terror in which I rush around the cell jerking my arms about . . . to remind me of a world beyond that is various and rich (p. 93).

The magistrate empathises with his so-named enemies; the empire responds with imprisonment without trial.

By the novel’s end, the barbarians fail to make an explicit appearance in the town. Now free, the magistrate retreats to a room and ponders whether an attack will ever happen, “when the barbarian is truly at the gate” (p. 169). The absence of the barbarians — their life in the shadows of the empire’s jurisdiction — raises questions surrounding the empire’s purpose. The answer, as the novel’s title suggests, is to maintain an idea of the enemy, an antagonist, to legitimise the nation-state and give it purpose. No barbarians — no political schema to justify the empire’s existence.

Coetzee’s allegory of oppressor and oppressed shows that the empirical project can never persist everlastingly. The power of empathy “in the hollow of one’s bones” creates the crucible for a crisis in one’s conscience. The oppressor cannot go on torturing the innocent forever. To do so only foresees the empire’s slippery hold on political power.

SOURCES

[1] Waiting for the Barbarians. By J. M. Coetzee. London: Vintage, 1980. 978-0-099-46593-5.

[2] Mythologies. By Roland Barthes (trans. by Annette Lavers). London: Vintage, 2009. 978-0-952975-0.

| |

| A remarkable book... J. M. Coetzee's 1980 novel criticised empire |

Comments

Post a Comment