On Happiness

To be uplifted means to be happy – but only in a momentary sense. In day-to-day life we experience regular feelings of fresh hope. They come and go, are fleeting things. Yet when we define happiness as an idea, we refer to the exact opposite: something stable, everlasting, irrefutable – chiefly, an idea taken for granted. A statement like, “I am happy” suggests acute permanence, being grammatically in the present perfect. The verb “to be” establishes a solid state, a way of being which looks unflinchingly toward the future. But our grammatical consciousness misconceives the truth. When we invoke “happiness”, we immediately disconnect with the material world, and venture into the abstract, thereby proposing a concept which refuses to be measured in quantitative terms.

We have to remix the truth, principally in qualitative terms. Here is an alternative: measure happiness as something strictly relative – not universal. A philosophic and psychological entity that rejects all stable brackets, both round and square, opening up to endless interpretation – to multifarious, slippery definition. Everyone contributes. We suddenly move away from accepting happiness as a given, relieving all pressure to conform to concrete visions of what it means to be happy. Concrete visions that breed negative possibilities. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, a wicked example, paints an extreme picture of a universal concept’s danger. In a mock-utopian society, people receive pharmaceutical happy pills to maintain joy. Via substances, they manipulate their emotions to live false realities. So by listening to the individual’s version of happiness and its philosophy, we avoid such daymarish possibilities, such dystopian futures.

Especially in the wake of Covid-19 measures. Second-level impacts of the pandemic have introduced a mental health crisis, one where journalists eagerly report drops in psychological well-being, extending to cases of “pandemic burnout” (that is, natural reactions to an intolerable situation) [1]. In this day and age we have to retune our ears to what happiness means in a world of reduced joy. We require a subjective corrective – a means of recalibrating happiness to fit low-grade adversity.

Happiness means different things to different people. This is less obvious than you imagine. Meditating on this topic some 1,600 years ago, Augustine of Hippo devised a useful method to reduce Happiness (with a capital H) from its high-and-mighty status as a big idea to the level of individual drives. We all experience happiness differently; as such Augustine’s method provides an inverse pyramid, reaching its conclusion in first-person experience.

We begin with a longing, a searching feeling for what happiness generally means. We all long for happiness, says Augustine, which sows the seeds of processional contemplation. To start with, happiness as an idea must be vague: “[u]nless we had some sure knowledge of [happiness],” he says, “we should not desire it with such certainty”. Second comes the testing stage. Ask two people if they would like to join the army, one will likely answer, Yes; the other, No. But ask them if they want happiness, they will probably both answer, Yes. This welcomes the subjective corrective: different people find happiness in different things. If we conflate happiness with joy, we each know what this feels like – what this means – on a personal level. (Everyone has a joyous memory, for instance.) As long we adhere to a moral good, humankind should continually pursue these states of joy (just as we pursue individual goals) [2].

When we start to think this way, we think of the happiness of others. The subjective corrective allows us to understand these moments better. Happiness no longer passes through us; instead, we pass through happiness, riding with both hands gripping tight to life’s steering wheel, driving on our own terms.

Notes:

[1] Caroline Williams, “Heading for Burnout”, in New Scientist, no. 3320 (2021), pp 34—38.

[2] Saint Augustine, Confessions, trans. by R.S. Pine-Coffin (Penguin: London, 1961), p. 228.

|

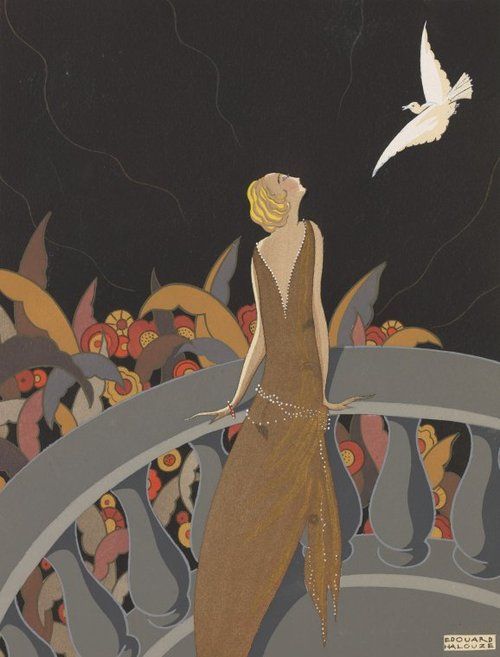

| The Messenger by Edouard Halouze, c. 1920. |

Comments

Post a Comment