Twentieth-century Trauma and the Russian Collective Mind

For new recruits and seasoned veterans

alike, the Great War (1914-18) was a novel experience. New technologies

reshaped frontline warfare, as rank-and-file men and women dealt with new

realities on the European battlefield.

Physical reality mirrored the War’s mental

effects. Varda Wilcox, assistant professor in European history, says that

soldiers on the frontline ‘underwent a series of terrible and physical

emotional experiences’ [1]. What kept soldiers going, she argues, was the

presence of courage-boosting ideas, such as ‘comradeship’. Collective values like patriotism (an idea that official propaganda liked to exploit) also

promoted resilience, as severe punishments for ‘cowardice’ kept anti-war

behaviour at bay. On all fronts, the soldier’s conception of what they were fighting for kept war efforts moving.

The mental cost of the War is

well-known, resulting in the first popular recordings of ‘shell-shock’, or

post-traumatic stress, among its survivors. Nations, such as Great Britain and

France, dealt with the Great War’s traumatic legacy adequately, but some

countries grappled with it better than others.

In eastern Europe, for example, things

worked differently. Catherine Merridale, a scholar, has discussed the

remarkable absence of post-traumatic stress in twentieth-century Russia. She

argues that this was a symptom of cultural stigma, rather than an absence of Russian trauma patients.

This stigma arose from two issues:

first, a Russian social system which devalued the individual in favour of the

collective; second, the construction of a heroic myth during wartime, claiming that shell-shock

was a ‘personal weakness’ on the part of the sufferer – a test of one’s

‘manhood’.

Stalinism amplified these national

traditions. The results, Merridale claims, extended beyond the early twentieth-century.

‘A people accustomed to silence’ influenced collective responses to individual

trauma well into the declining years of the Soviet regime [2].

In the 1980s, Merridale interviewed the Great War's Russian survivors. To explain the absence of public trauma, many relied on an argument of Russian

exceptionalism – that the Russian mind was stronger than the West.

In this way, suppression was a survival strategy. Throughout the twentieth-century, a Russian style of stoicism

pervaded social attitudes because it legitimated life under a repressive

regime. ‘The Soviet myth of heroism,’ Merridale says, ‘was born as soon as the

[Great War] broke out. [. . .] Coping, indeed, provided people with a sense of

purpose and even pride’ [3]. In order to survive the everyday horrors of Soviet

repression, Russian citizens valued a tight-lipped response towards poor mental

health: collective solidarity trumped individual suffering.

Russia’s case is an object lesson in

how a social/cultural system can distort reality. A revolutionary regime

reshaped the people’s understanding of the Great War and its inevitable outcomes, including its human costs. As a result, a survivor's culture that repressed individual emotions emerged, changing Russia's mental landscape forever.

Notes:

[1] Varda Wilcox, ‘Combat and the

soldiers’ experience of the First World War’, British Library (2014).

[2] Catherine Merridale, ‘The

Collective Mind: Trauma and Shell-shock in Twentieth-century Russia’ in Journal

of Contemporary History, 35/1 (2000), p. 55.

[3] ibid., p. 49.

|

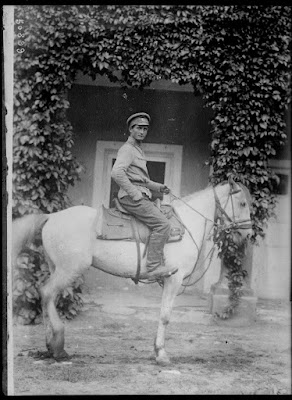

| Female member of the Russian imperial guard, July 1917 © Bibliothéque nationale de France |

Comments

Post a Comment