Irony and Ian McEwan's 'Nutshell'

In 1502, ‘irony’ received its first mention

in English print. Irony, the anonymous author said, refers to 'grammar by the

which a man says one [thing and] gives to understand the contrary’. As such, irony contrasts appearance with reality, directing our attention to the

level of incongruity between words and their meanings. On a surface level, irony is an attempt to state the very things it does not mean. Irony pursues truth – it usually has a comic effect, noting the absurdity of everyday

things.

In Nutshell, Ian McEwan uses

verbal irony to craft a fictional foetus’s voice. As a first-person narrative,

the novel tells a murder tale through the observations of a nine-month-old baby

still in the womb of its mother. Irony is key to the novel’s

inception, for a talking foetus is an impossibility, let alone imaginable.

Nutshell’s narrative is a discussion of the foetal

condition. The narrator, an autonomous baby, wonders what it feels like to

be human. The novel’s epigraph is from Hamlet, and just as Shakespeare

explores father/son metaphysics in Hamlet’s cast of characters, McEwan

attempts to investigate the everyday conditions that pre-date worldly life. The baby

pleads: ‘Grant me all the agency the human frame can bear, retrieve my young

panther-self of sculpted muscle and long cold store, direct him to the most

extreme measure’ (52). Helplessness is key to the foetal state. Fundamentally,

the foetus is at mercy to the world’s decisions. Without the experience of

causation or action, Nutshell’s foetal narrator can only dream

of being human. This is the extent of its bearing on the world: it can

never act the same way the ‘human frame’ can.

McEwan plays with everyday colloquialisms

to heighten our sense of the foetus’s situation – namely, the desire to be born

and grow into an autonomous human. In the opening paragraph, our narrator

admits that he (it’s a boy) ‘once drifted in my translucent body bag . . . [but]

that was in my careless youth’ (1). Later, he learns of his mother’s plans to

murder his father, but the burden of knowledge combines with the inability act. This torments him. ‘I see no scheme, no plausible route to any conceivable

happiness. I wish never to be born’ (75). Such commentary inverts humanity’s

dilemmas and remixes them, addressing the problems of pre-birth. Irony makes the

foetus’s voice believable – as controversial as this may be, ironic language makes

the foetus human.

For the most part, the use of such

techniques allows McEwan’s speculative fiction to work. Unfortunately, he also manages

to break the spell and destroys the reader’s confidence in the story.

Nutshell suffers from pretension. In a key

passage, the foetus reveals that his mother is a functioning alcoholic.

Resultantly, the foetus indulges in high-flown critiques of the wines she

drinks, sounding more like a restaurant critic than an unborn child.

Trudy and I are getting

drunk again [. . .] After a piercing white, a Pinot Noir is a mother’s soothing

hand. Oh, to be alive while such a grape exists! A blossom, a bouquet of peace

and reason. No one seems to want to read aloud the label so I’m forced to make

a guess, and hazard an Échezaux Grand Cru. Put . . . a gun to my head to name

the domaine, I would blurt out la Romanée-Counti, for the spicy cassis and

black cherry alone. The hint of violets and fine tannins suggests that lazy,

clement summer of . . . (51)

And so on. McEwan’s personal interests

in wine tasting gets in the way of Nutshell’s story. Such indulgent

episodes reveal the level of middle-class male authorship that infects the

foetus’s fictional world. Although Nutshell does a good job

in telling a gripping tale, it fails to be entirely convincing.

Source:

Nutshell. By Ian McEwan. New York: Doubleday,

2016. 978-0-385-54207-4.

|

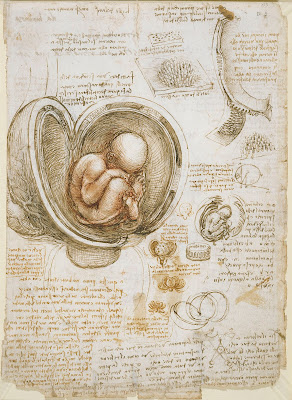

| Studies of the Fetus in the Womb by Leonardo da Vinci, c. 1511 (chalk on paper) Royal Collection, London |

Comments

Post a Comment