Vivid Faces

In 1920, the Irish Republican, Muriel MacSwiney, began her public tour of America. Delivering lectures on

British rule in Ireland, she told the American Commission that ‘[m]y parents

are not quite like myself’ (p. 330). Following the death of her husband, the

hunger striker, Terence MacSwiney, Muriel went on to work for various socialist

causes in Europe until the end of her days. For her, as for many young

nationalists, radicalism was a firmly entrenched mind-set. A sense of

self-purpose and self-fulfilling prophecy divided her from her forbearers. The Republicanism

of her parents was outdated, obsolete and on the wane.

MacSwiney’s statement characterises how

revolutionary nationalists perceived themselves in early twentieth-century

Ireland. Using letters, diaries and newspapers, Roy Foster traces the thoughts

and feelings of the generation that rebelled against British rule in Easter

1916. Early in the book, he outlines his thesis.

For many, young obscure

Irish people in the opening years of the new century shared a sense that change

was afoot, and that their generation would embody it. [. . .] [W]e might perhaps

discern a “generation of 1916” in Ireland, reacting against their fathers. (pp

6-7)

Bent on self-transformation, these new

nationalists felt part of a greater destiny. They sought to destroy what they saw

as an Anglicized identity in pursuit of a purer, idealised vision of Ireland.

In other words, the route of constitutional nationalism, then pursued by John

Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP) in Westminster, was totally ineffective.

Redmonites collaborated with the British government – and Foster’s so-called ‘revolutionary

generation’ found this unacceptable.

Radicalism encompassed various duties.

Culturally speaking, the Irish language was key to a Republican relationship

with the island of Ireland. Education was crucial. For instance, Gaelic League

summer schools paved the way towards Irish language classes, indoctrinating

students with revolutionary values to boot.

Admittedly, revolutionaries preferred

symbol over substance as many of the main players struggled with Irish Gaelic. Liam

de Róiste, another MacSwiney, admitted in 1906 that ‘I cannot say, with honesty,

that I know the Irish language. I am very conscious that native speakers, in

their hearts, laugh at my attempts’ (p. 50). The idea of Irish purity would be

hard fought. Revolutionaries found it much easier to Gaelicize their names, a ‘powerfully

symbolic act’ which allowed hardliners to don themselves with a mystic identity

(p. 120). Overall, the emphasis on the Irish language is one example of how the

revolutionary generation sought to cultivate nationalism.

Foster goes on to discuss the memory

of the Irish revolution and the disparity between the generation’s early ideas

versus the social conservatism that followed the formation of the Free State in

the early 1920s. Many felt betrayed by the revolution – that is, de Valera’s

Fianna Fáil government failed to stay true to the values of Easter 1916, imbuing

national memory with a false version of meanings. Republicans like the Quaker

writer, Rosamund Jacob, became disillusioned with de Valera, fearing the Free

State’s revisionist ties with Catholicism and the formation of a two-nation Ireland.

(The Free State constructed an identity which side-lined Protestant

Republicanism, forgetting Republicans like Jacob in a state sponsored narrative

of Irish history.) Foster notes how, over a hundred years later, debates

surrounding the Irish revolution continue to this day. Anyone who reads this

fascinating account of the individuals who set the revolution in motion will

benefit from its lucidity and precision, remembering the conflicts that such a

wild time in history caused.

Source:

Vivid Faces: The Revolutionary Generation

in Ireland 1890-1923. By R. F. Foster. Pp xxiii + 464 incl. 33 plates and

10 illustrations. London: Penguin, 2014. £10.99. 978-0-241-95424-9.

|

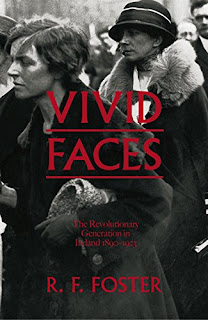

| Vivid Faces by R. F. Foster. Showing Muriel and Mary MacSwiney, c. 1922 |

Comments

Post a Comment