Steve Allen’s ‘Madonna’: Exploring a response to Madonna’s Erotica, c. 1992-93

All good Art (with a capital ‘A’) seeks

to challenge the norms and values of the societies we live in.

Released in October 1992, Madonna’s fifth studio album, Erotica, explored the idea of sexual freedom in a society which repressed such open behaviour. In an interview following the album’s

release, Madonna claimed that Erotica (in conjunction with the publication

of her picture-book, Sex) openly dealt with the 'repression that's going on in America right now'. ‘There’s a lot of really narrow-minded people’

out there, she said. Their opinions on how men and women should conduct themselves

were in desperate need of revision [1].

Erotica is a staggering performance. With its

clear vision and innovative handling of sexual themes in popular music, the

album is now widely held to be one of Madonna’s most important releases,

securing its place within her long legacy of original productions.

However, at the time, the album caused a lot of controversy. Whilst some journalists applauded Erotica for its artistic merits, others panned the album for its so-named ‘disreputable’ subject matter. Outsiders attacked the album for its moral decadence and argued that Erotica’s release signalled a general decline of wider values in the West. Madonna’s enemies tried to blacken her character, espousing an ultra-conservative worldview to brandish the aesthetic value of her public persona.

However, at the time, the album caused a lot of controversy. Whilst some journalists applauded Erotica for its artistic merits, others panned the album for its so-named ‘disreputable’ subject matter. Outsiders attacked the album for its moral decadence and argued that Erotica’s release signalled a general decline of wider values in the West. Madonna’s enemies tried to blacken her character, espousing an ultra-conservative worldview to brandish the aesthetic value of her public persona.

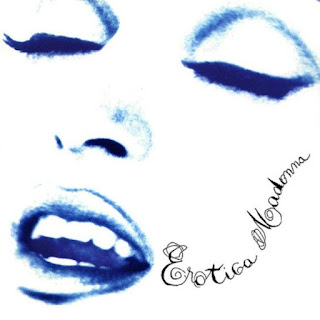

|

| Erotica by Madonna (Maverick & Sire Records, 1992). |

The prominent American television star, Steve

Allen, provided one such hostile commentary. In summer 1993, Allen embarked on

a full-frontal assault against Madonna’s place in the music business. He began

by making the claim that Madonna, when compared to such figures of ‘remarkable

gifts’ such as Barbara Streisand (!), was truly talent-less [2].

Allen argued that Madonna has

succeeded not because of her talents, but because ‘of her neurosis, her moral

weaknesses, her willingness to prostitute herself for fame and money’, and, most

of all, the fact that she ‘falls short of the moral standards we [Americans]

sincerely profess’ [3]. Instead, she ‘flaunts her disdain for

these standards’ [4]. With acid-tongued rhetoric, Allen deprecated Madonna for

rejecting the value system he so cherished. The importance of such a point, he

claimed, relied on the idea that Madonna was a role model for ‘millions of

impressionable teenagers’ [5].

Allen’s article is a classic case of

an attempt to create a ‘moral panic’. The sociological scholar, Stanley Cohen, coined this term, studying the adverse reactions against mods and rockers in 1960s Britain. Using this term, he observed the processes and

mechanisms that led to the construction of popular opposition to subcultural groups. Through media channels like print and the popular

press, Cohen said elites generate a ‘moral panic’ to villainise the people they are at ideological ends with. One of the basic requirements for the

development of a ‘moral panic’ is to target someone who is a suitable enemy, or

‘folk devil’, who can be easily denounced. Then, the panic requires a suitable

victim, such as morality [6]. In Madonna’s case, enemies like Allen tapped into

the established tropes of moral language to stir panic over the values that her

Art demanded.

Allen focused on sexual morals to

provoke popular opposition against Madonna. He argued that Americans should be

ashamed about the open promiscuity that her media output, such as Erotica

and Sex, celebrated. Americans were wrong to

market her standard of ‘anything-goes sex’, which destroys ‘honourable

traditions’ of courtship, and – worst of all – glorifies Madonna as a ‘public

slut’ [7]. Using such language, Allen zones in on a popular discourse which shames and deprecates female sexual promiscuity. He embeds his argument

in a gendered ideology that aspired to ruin Madonna’s reputation.

Yet this is the very issue which Madonna tackled

in her creative output. Erotica’s themes and lyrics made the case that the

traditional association between promiscuity and immorality was false. Her

celebration of candid sexuality disclaimed the views of people like Allen.

Indeed, Madonna’s position is more profound. Scholars have shown that such associations tend to be socially constructed. The American philosopher, Michael Humuer, argued that we must be wary of these traditional values, especially since there is ‘extensive variation in perceptions of morality across cultures’ [8]. Humuer pointed out that, really, there is nothing wrong with careful promiscuity. It is something far more moralistic than, say, something as extreme as murder [9]. Madonna was in the right; Allen was in the wrong.

Indeed, Madonna’s position is more profound. Scholars have shown that such associations tend to be socially constructed. The American philosopher, Michael Humuer, argued that we must be wary of these traditional values, especially since there is ‘extensive variation in perceptions of morality across cultures’ [8]. Humuer pointed out that, really, there is nothing wrong with careful promiscuity. It is something far more moralistic than, say, something as extreme as murder [9]. Madonna was in the right; Allen was in the wrong.

|

| Steve Allen in his heyday. © Britannica. |

In his attempt to create wider

disapproval of Madonna’s Art, Allen exhibited the characteristics of ‘moral

panic’. He weaponised a shared code of morality to defame both her music and

public presence. Such positions should warn us of the tactics people employ in their attempt to alter our perceptions of the creatively innovative.

Notes:

[1]

Madonna quoted in Joe Lynch, ‘Madonna’s “Erotica” Turns 25: An Oral History of

the Most Controversial ‘90s Pop Album’ Billboard (20 Oct. 2017) [https://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/pop/8006663/madonna-erotica-album-sex-book-oral-history

accessed 16.10.19].

[2]

Steve Allen, ‘Madonna’ Journal of Popular Culture, 27/1 (1993), p. 3.

[3]

ibid.

[4]

ibid.

[5]

ibid., p. 4.

[6] Keith

Gilbert, ‘The Antithesis of Humankind’ Cultural and Social History, 10/1

(2013), pp 130-31.

[7]

Allen, ‘Madonna’, pp 10-11.

[8]

Michael Humuer, ‘Values and Morals: Outline as a Skeptical Realism’ Philosophical

Issues, 19 (2009), p. 123.

[9]

ibid., p. 124.

Comments

Post a Comment